The first victim of austerity? The impact of the worldwide ’neoliberal turn‘ on the breakdown of the Yugoslav Federation

The Essay describes the breakdown of Yugoslavia as a result of the destruction of the welfare system and thus the social fabric by austerity measures. It tries to show how European and worldwide neoliberal politics had a major influence on the economic downturn and thus lead to the emergence of so far unimportant ethnic differences, to nationalism, and finally to war.

edit: my wordpress-skills aren’t quite enough solve all the formating and style problems of the article, sorry for changes of typeface and some red lines in the online version!

„the domestic order of socialist Yugoslavia was strongly influenced by its place in the international order: its geopolitical location, its patterns of trade, and foreign alliances, and the requirements of participation in the international economy and its various organizations.“ (Woodward 1995: 16)

1. Introduction

The breakdown of Yugoslavia and the following war is commonly described as a result of (historical) ethnic tensions, excessive nationalism, an ineffective federalist system and repression of freedom under socialism (see Woodward 1995: 7-8 or wikipedia: Yugoslav wars). While conflict parties on all sides surely showed a frightening racist and nationalist face and without denying the economic problems of the socialist period, I argue that one of the most important reasons for the meltdown is usually omitted: The destruction of the welfare system and thus the social fabric by neoliberal austerity politics. Even US based intelligence company Stratfor (not know as a very critical or leftist organization) writes in an internal Email published by Wikileaks, that “the IMF [International Monetary Fund] austerity measures imposed on Yugoslavia was [sic] in part to blame for the start of the war there”(Wikileaks/Strategic Forecasting, Inc. 2009). As I will show in Part 3, there was a worldwide neoliberal turn of economic policy after the economic downturn in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis that also changed the EU and its dealings with Yugoslavia. The kind of Austerity politics that have been implemented since 2008 by the Troika (European Commission, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund) in Greece and Spain had already been forced on Yugoslavia from the 70s on. They aimed at reducing the foreign trade deficit by budget cuts in the welfare system and government institutions and by opening the country to foreign investment. But instead of increasing the economic stability of the Federation, they only lead to increasing foreign debt, massive unemployment and the dismantling of social protection systems. As economic problems were always answered with even more severe austerity measures, the economy spiraled downwards to a point where “One million people were officially registered as unemployed. The increasing rate of unemployment was above 20 percent in all republics except Slovenia and Croatia. Inflation was at 50 percent a year and climbing. The household savings of approximately 80 percent of the population were depleted“ (Woodward 1995:73). As the people struggled for securing basic necessities and services they couldn’t afford any more, nationalist movements became more and more appealing. Tensions arose out of the different abilities of the republics to compete in the global market. While Slovenia and Croatia were relatively well off, the situation in the other republics was even more dramatic. The former accused the latter of inhibiting the growth and competitiveness of their industry and saw independence as a way to improve their condition. It seems plausible that nationalist symbols and a new interpretation of historical developments arose as a justification for this separation. Considering the severity of the problems and imagining how it must feel to live in a once successful but now rapidly deteriorating economy it seems that Susan Woodward is correct when she says “to explain the Yugoslav crisis as a result of ethnic hatred is to turn the story upside down and begin at its end.“ (Woodward 1995:18). Thus, I will begin at the beginning and try to show how European and worldwide neoliberal politics had a major influence on the economic downturn and thus lead to the emergence of so-far unimportant ethnic differences, to nationalism, and finally to war.

2. Yugoslavia, Part I

Self-management and the balance of powers

When the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was founded in 1946 by communist partisan forces, its constitution was closely modeled on Leninist ideas of the state and very similar to that of the USSR. But just two years later, in the Tito-Stalin split, it became an independent communist state and refused to align itself with either the capitalist nor the socialist bloc. Its economic and social policy afterwards reflects this fragile status between the two systems, trying to formulate its own independent agenda. It was in many respects a child of two worlds. To protect itself from military aggression and build economic connections, Yugoslavia became an observing member in both western and communist international Organizations. It managed to obtain an observer status in the (communist) Council for Mutual Economic Assistance and the (communist) Warsaw Treaty Organization as well as the (western) OECD and it met the requirements of the (western) General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). In Addition, Yugoslavia was in major player in the Non-aligned-Movement, trying to build a coalition of states that refused to take sides in the cold war.

The economic policy had large “socialist” elements, the most visible of these worker self-management. In a unique move, the communist leadership transferred a huge amount of power to local authorities and councils of workers that were enabled to decide on a wide range of matters. “Local governments were responsible for consumer markets, welfare, housing, local roads, elementary schools, health care and unemployment” (Woodward 1995:39) and ‚councils of producers‘ were installed “as legislative chambers on all levels of the state” (Unkovski-Korica 2015:26). In the public sector, workers were guaranteed to receive equal pay for equal work, there was a minimum wage in all sectors and substantial welfare and health-care system. Unlike other communist states, Yugoslavia had a significant private sector. Social inequality was not along ethnic lines, but depended mainly on if you were employed in the public sector and were entitled to access the healthcare and welfare systems connected to it, or in the private sector without many of these benefits. As most of the jobs were created in urban areas, rural environments were also significantly poorer. But overall, the Federation was economically prospering, it was one of the fastest-growing economies of the 1950s and people enjoyed relatively high living standards (see Unkovski-Korica 2015). Yugoslavia’s middle-class could freely travel the world and all its citizens enjoyed a freedom that was unknown in other “socialist” states. Yugoslavia was also a major player in international politics. It had ties to both western and eastern superpowers and was a major leader of the Non-aligned-Movement that refused to take sides in the cold war. But very soon after, the economic policy of the ruling party, the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (LCY) changed and led the country into a debt trap it never recovered from. To understand why the LCY embarked on a export- and market-orientend strategy that was ultimately incompatible with self-management, one has to consider the worldwide trend towards a different economic system, a development I will call the “neoliberal turn”.

3. The worldwide neoliberal turn

3.1 Class war – from above

After World War II, nearly all ‚western‘ economies were growing rapidly, production was getting more and more efficient and new consumer goods became widely available. Despite other differences between the US, Japan and Europe „what all of these various state forms had in common was an acceptance that the state should focus on full employment, economic growth, the welfare of its citizens, and that state power should be freely deployed […] to achieve these ends. Fiscal and monetary policies usually dubbed ‚Keynesian‘ were widely deployed to dampen business cycles and to ensure reasonable full employment“ (Harvey 2005: 10). In a ‘class compromise’ with Capital, Trade unions were integrated into the regular institutions of the states and had a major influence “that curbed the power of capital and extended the power of labour even into the workplace” (Harvey 2005:112, see also Apeldoorn 2002: 63-65) Through trade liberalisation under GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) competition on the global market began to grow, but national regulations according to foreign trade and investment limited this competition. It seems that the situation in Yugoslavia was very similar to that of most emerging and developed countries, only that there was an even stronger influence of the working class which led to the introduction of the “self-management”-approach.

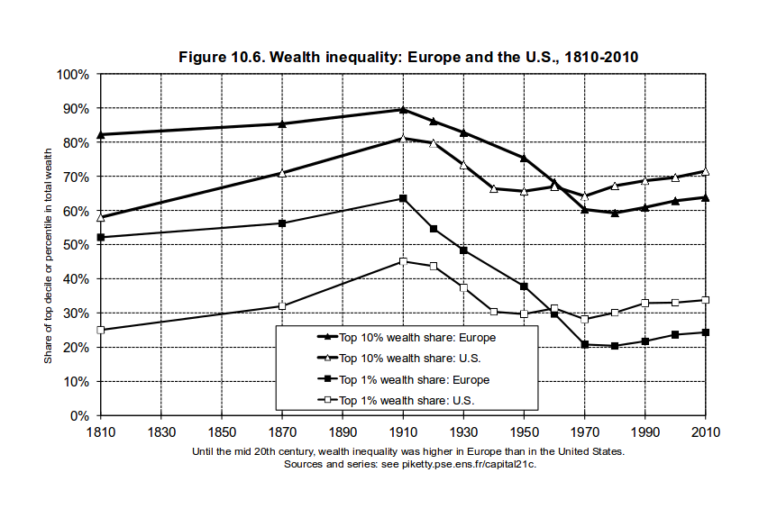

Things started to change when “at the end of the 60s for the first time productivity gains began to decline whereas wages continued to rise – resulting in a falling share of profits within the income distribution” (Apeldoorn 2002: 65), because of the Trade Unions‘ strong bargaining position. Harvey argues, that the “upper classes everywhere felt threatened“ (Harvey 2005:15) by this developments, as “real interest rates went negative and and paltry dividends and profits were the norm” (ibid). Piketty shows this relative loss of economic wealth in the upper classes happened from 1910 onwards but was reversed in the 1970s (see Table 1). This reverse happened because, in an ironic reference to Marx, the capitalist class became aware of its common interests and started to wage class war – from above (see Harvey 2005:43,44). Already introduced in works like F.A. Hayek’s “The road to serfdom”(1944) the concept of Neoliberalism that did have much influence so far became their main ‘weapon’. As defined by Harvey: „Neoliberalism is in the first instance a theory of political and economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade“ (Harvey 2005:2). It soon become apparent, that only a very limited number of people profited from this kind of freedom, but capitalist organizations took great efforts to promote the new paradigm. In 1972, the US-American Chamber of Commerce started to heavily expand its base of corporate members and started a free market and pro-business lobby campaign. In the same year, the US ‚Business Roundtable‘ was founded and its members “spent close to $900 million annually (a huge amount at that time) on political matters.” (Harvey 2005:44). The pro-neoliberalism movement had its first successes in the US, but soon expanded worldwide.

3.2 The neoliberal turn in Europe

The advocates of neoliberalism also managed to change the economic policy of all European Countries, albeit not without a struggle and not as much as in the US, China and Japan. After WWII, all European governments had expanded their welfare systems and thus public sector expenditure. When growth and profits began to fall in the 60’s, European countries first experimented with nation-state-centered solutions to improve their economic condition. Apeldoorn identifies three different approaches: The British, the German and the French model. (Apeldoorn 2002:72-77) Britain under Margaret Thatcher embarked on a neoliberal course with a firm commitment to international free trade, reliance on market mechanism with little interference from the state and financial deregulation. Germany was also “fully committed to international free trade” (Apeldoorn 2002: 74), but in its “social” market economy preserved a relative high degree of Union power (“Mitbestimmung”) and its banks were more closely tied to the industry and less liberal than the British banks. France first tried to nationalize huge parts of the economy and undertook a big Keynesian reflation programme. Here, the state retained a strong influence over economic policies and market mechanisms were limited to a relatively small degree.

In the 80’s, most governments began to acknowledge that a “European” solution to the economic crisis was necessary and began to relaunch efforts to create an internal market and what in 1992 became the EU. The different national models of capitalism sparked a controversy about what kind of Europe was to be created. Jacques Delors, president of the European Commission from 1985-1995, envisioned a ‚European social model‘ that combined “the competitive market with a system of social solidarity, all in a long-term perspective of sustainable growth and welfare” (Apeldoorn 2005: 79), resembling the ‘german’ model mentioned earlier (which saw a considerable protection of the interests of labour). But when the European Community was formally established with the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, very little of this protection remained and the EC had become a mainly neoliberal project with “free” trade, “flexible” labour markets and huge privatization efforts. Apeldoorn claims, that “the failure of the social dimension must be attributed not only to the intransigence of the British opposition […], but also to the strong resistance put up by the transnational business lobby” (Apeldoorn 2005: 148).

What is known as “lobbyism” today, was most likely born, or at least heavily increased in the years between WWII and the Maastricht treaty. Neoliberal Think Tanks like the Mont Pèlerin Society (1947) emerged and shaped public discourse. Similarly to the US, the capitalist class became aware of their common interest and how they could pursue them. One example is that “from the mid-1970s onwards, the Swedish Employer’s Federation […] launched a propaganda campaign against excessive regulation and for the increasing liberalization of the economy “ ( Harvey 2005: 113) A little later, in 1983, the European Roundtable of Industrialists was founded, quickly established links to top politicians in the European commission (it was co-founded by Viscount Etienne Davignon “at the time one of the vice-presidents of the European Commission and charged with industrial affairs” (Apeldoorn 2005: 84) and became the single most influential interest group in Europe. Apeldoorn quotes former Former Commissioner Peter Sutherland, who states that: “I believe that it [the ERT] did play a significant role in the development of the 1992 programme. In fact one can argue that the whole completion of the internal market project was initiated not by governments but by the Round Table, and by members of it” (Apeldoorn 2000: 168). As the programme of the European Union was increasingly shaped by neoliberal think tanks and business lobby organizations, Union Power vanished and with it, the Vision of a “social” Europe. This also changed policy towards other countries in Europe and the possibility of transnational interventions of organizations like the IMF (International Monetary Fund), as we will see in the case of former Yugoslavia.

4. Yugoslavia, Part II

4.1 Orientation on the export market

The turn to neoliberal economic policies also had its influence on Yugoslavia. The economic strategy of the LCY shifted to more market- and export-oriented policies. According to Unkovski-Korica “because a growing economy was important for the maintenance of national independence, quick returns on investments became ever more central to the calculations of the Yugoslav communist leadership” (Unkovski-Korica 2015:28). A series of new laws based the income of workers on the success of their products on the international market instead of receiving a fixed income for a certain type of work. This lead to a (probably intended) rise in competition between different enterprises, but also to a (probably less intended) widening income gap between the workers in different industries and republics. To reduce the foreign trade deficit, the YLC tried to develop the industrial areas (that were mainly situated in Slovenia and Croatia) and the agricultural hubs (mainly found in Serbia). This happened at the expense of large areas of Bosnia that saw a huge decline in subsidies from the Federation (and subsequently in living standards). This unequal distribution sparked controversies between the republics and the Federation and received criticism from all sides. The more industrial (and thus more successful on the world market) Republics Slovenia and Croatia feared that their own progress could be retarded by the other republics (See Unkovski-Korica 2015:31). The other republics probably understood this as a lack of commitment to the integrity of the Yugoslav Federation and warned of the dangers of decentralization. For example, “Bosnia complained about its Development Fund allocation and Albanians in Kosovo and Macedonia protested long years of neglect and oppression in 1968” (Unkovski-Korica 2015:33). Although most likely aware of the tensions, the YLC continued their course by restoring hierarchies in the workplace and dismantling the self-management system by introducing a new “business board” in all enterprises in 1969 to increase their competetiveness. In 1970 and 1980 they signed “free trade agreements” with the EEC (European Economic Community) which “accelerated dependency on capital and hard currency imports to finance export growth” (Zikovic 2015: 48) and consequently borrowed huge amounts of foreign currency, most dollars, “to import advanced technology to improve its (Yugoslavia’s) competitiveness” (Woodward 1995: 47).

These loans became a major problem in the worldwide recession after the oil prices shock. Firstly, trade liberalisation under the EEC was a one-way-street as the other european countries “raised trade barriers in exactly those areas where Yugoslavia enjoyed competitive advantage (steel, textiles, tobacco, beef and veal)” (Zivkovic 2015: 48) and the products of the machinery bought by these loans could not be sold at good prices any more. Secondly, as the IMF changed its policy towards monetary stability in 1979, “the interest rate on the U.S. dollar skyrocketed, and with it the foreign debt of all countries holding debt in those dollars” (Woodward 1995:48) leading to a even higher financial burden for Yugoslavia.

4.2 The Austerity regime of IMF and EEC

Unable to compete on the global market and suffering from an increasing foreign debt, the Federation was on the “brink of bankruptcy” (Unkovski-Korica 2015: 39). To avoid not being able to serve Yugoslavia’s debt obligations, the LCY took more short-term loans from the IMF, receiving the largest loan in the history of the IMF in 1981. The IMF and the EEC (European Economic Community) presented the LCY a programme they had to follow in order to receive these loans and and promised them they would recover economically if they would follow it rigorously. The programme was basically one of austerity and also “one of the first structural adjustment programmes in the world” (Zivkovic 2015: 49). The Yugoslav Federation abandoned Food and basic commodity subsidies to decrease import, “prices rose by one-third 1983” (Woodward 1995: 51). All imports not critical to production were prohibited. Higher interest rates on foreign currency bank accounts were meant to provide the Federation with more liquidity. Investment in social services and infrastructure were completely frozen to minimize spending. All firms were obliged to lay off workers if facing losses to improve their competitiveness (see Woodward 1995: 51).

Together, these measures lead to massive unemployment of up to 50% in some republic and to a general feeling of having to survive in an increasingly competitive and hostile environment, even in the wealthier republics. 25% of Yugoslavia’s inhabitants were considered to be under the poverty line (Woodward 1995: 52). People may have coped with rising unemployment and scarce resources if there had been a social net like twenty years ago, but those welfare institutions had also fallen victim to austerity measures and could do very little to relax the situation. As these were gone, people were desperately searching for new ways to protect themselves and their familes and also for the reasons behind this sudden deterioration of their living standards.

4.3 The end of solidarity

The IMF had dismantled the welfare institutions but realized that a strong central government was needed for the economic policy change it demanded. It thus ”began to tie conditions for new credits to political reform” (Woodward 1995:74). The “IMF and EEC demanded the recentralisation of the Yugoslav federation to drive through macroeconomic stabilisation and financial discipline” (Zivkovic 2015: 49). It seems very likely that this very demand was the catalyst for the split-up of Yugoslavia and the consequent war. The reason why the demand for recentralization proved to be so destructive was the fierce competition on the international market and the very unequal position on this market of the different republics.

Slovenia had a strong, export oriented economy which was able to compete on the global market and imported most of its primary commodities from outside of Yugoslavia. Serbia and its autonomous regions Kosovo and Vojvodina on the other hand, were still largely agricultural and more dependent on the internal market and also redistribution on the federal level to develop their economy. This redistribution on the federal level and the expenses for the federal army were increasingly seen as an unnecessary burden by the Slovene Leadership. Together with the Croatian government, it opposed expenditures for defense and development in the south with a neoliberal „trickle-down“ reasoning. “They argued that productivity was declining because redistribution sapped the incentive of firms and workers and that growth and exports would revive fastest of firms that were profitable (and the republics in which they were located) made decisions on investment“(Woodward 1995:69). It was in this climate of dwindling internal resources, increasing debt and vanishing solidarity that nationalist ideas became more and more appealing. For Slovenia, national independence was a way to get rid of the obligation to contribute to the Federation. For Serbia, the integrity of the Federation and the IMF reform course seemed the only way to a stable economy, but it had to face growing protest, especially in Albania. The Serbian government’s refusal to accept the separatist movements in Albania, Slovenia and Croatia was increasingly seen as an attempt to dominate the others republics and thus its people. Although Slovenia and the international creditors (IMF and EEC) had opposite aims in the centralization-decentralization debate, “they both attacked the stabilizing political mechanisms of the socialist period” (Woodward 1995:80). When Slovenia failed to convince the other republics with its idea of more independent republics at the Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists in January 1990, it left the League for good. The remaining parties could not agreed on how to deal with Slovenia’s exit and the LCY was effectively dissolved (see Woodward 1995: 115). When the army – in an attempt to protect the integrity of the Federation – took actions against protesters in Croatia, killing twenty eight people, political tensions escalated further. In the same year, the following multiparty elections strengthened nationalist parties, like the HDZ of Franjo Tudjman which campaigned for “sovereignty” and the SPS of Slobodan Milosevic which won with the slogan “With us there is no insecurity” (see Woodward 1995:120-121). The following escalation of the conflict between those parties is not part of this essay, but it should have become apparent how they themselves were the product of the economic situation in Yugoslavia.

5. Conclusion

A neoliberal coup d’etat?

Woodward claims that the European governments did very little to resolve the Yugoslav crisis before the war began in earnest (see Woodward 1995:152). She explains this fact with the focus on other problems, like to situation in the middle-east, all the other European countries had, although an emerging war in a nearby country does not seem like a minor issue governments would normally more or less ignore. One may have to take into account, that around the 1970s “Communist and socialist parties were gaining ground, if not taking power, across much of Europe […] There was, in this, a clear political threat to economic elites and ruling classes everywhere” (Harvey 2005: 15) It seems possible that there might have been little interest in resolving the crisis in Yugoslavia from the point of view of the capitalist class, as this might have given the Yugoslav “middle-way” project a certain prestige that would have questioned the hegemonic power of the neoliberal elite.

Apart from what the motives of the IMF and EEC behind the austerity regime were, I doubt the war in Yugoslavia would have happened without it. The question if the breakdown of Yugoslavia in the wake of the neoliberal reforms was an unforeseen side-effect of a genuine believe in the wisdom of ‘the market’ or if the neoliberal elites were aware of the likely consequences of such an austerity regime and welcomed them in order to complete the restructuring, can not be answered with my current knowledge. Harvey agrees with Dumenil and Lévy who say that “neoliberalization was from the beginning a project to achieve the restoration of class power” (Harvey 2005: 16) and if you see it this way, the restructuring of the Yugoslav Federation was successful, the self-management approach seems completely discredited. The total collapse might have been necessary to complete the neoliberal reorganisation, because “It is only when the internal power structure has been reduced to a hollow shell and when internal institutional arrangements are in total chaos, either because of collapse (as in the ex-Soviet Union and central Europe) […] , that we see external powers freely orchestrating neoliberal restructurings.” (Harvey 2005:117) With the richest 1% of humanity now owning more than all others combined (see Oxfam 2016), class war from above is still thriving but the neoliberal paradigm is also increasingly critizised. It would be interesting to research if people in former Yugoslavia are aware of the neoliberal project and what kind of alternatives are discussed at the moment.

6. Sources

6.1 Table

Source: http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capital21c/en/pdf/F10.6.pdf Access 15.09.2016

6.2 Literature:

Appeldoorn, Bastian van 2002: Transnational capitalism and the struggle over European integration. London: Routledge.

Harvey, David 2005: A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

van Apeldoorn, Bastian 2002: Transnational Capitalism and the struggle over European Integration. London: Routledge.

Oxfam 2016: 210 Oxfam Briefing Paper. https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/bp210-economy-one-percent-tax-havens-180116-summen_0.pdf Access 07.10.2016

Unkovski-Korica, Vladimir 2015: Self-management, Development and Debt: The Rise and Fall of the ‚Yugoslav Experiment‘. In: Horvat, Srećko and Ŝtiks, Igor 2015: Welcome to the desert of post-socialism: radical politics after Yugoslavia. London and Brooklyn: Verso.

Woodward, Susan 1995: Balkan Tragedy: chaos and dissolution after the cold war. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Wikileaks 2012: Strategic Forecasting, Inc 2009: Europe Analytical Guidance. https://wikileaks.org/gifiles/docs/54/5424835_-eurasia-europe-analytical-guidance-tier-3-.html. Access 08.09.2016.

Wikipedia: European Roundtable of Industrialists. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

European_Round_Table_of_Industrialists. Access 08.09.2016.

Zikovic, Andrea 2015: From the Market…to the Market: The Debt Economy After Yugoslavia. In: Horvat, Srećko and Ŝtiks, Igor 2015: Welcome to the desert of post-socialism: radical politics after Yugoslavia. London and Brooklyn: Verso.